Part One: A Tale of Phantom Quotes

As an editor, I specialize in nonfiction. I work with many clients who possess great expertise in their fields but who wouldn’t claim to be trained writers, so I tend to spend a lot of time verifying and documenting quotations. Here are just three that I’ve encountered in my editorial adventures lately—three that fall into the category I call “phantom quotations.” Please note that my use of these examples is in no way a criticism of the writers who included them: these quotations, or versions of them, appeared in early drafts and were not ultimately adopted in these forms. The point is not that the writers made mistakes. All writers, even the best ones, make mistakes. The point is that quotes like these are one of the very reasons the best writers always use editors: it’s important to have a second, objective pair of eyes that can spot and troubleshoot issues with quotations that inevitably arise.

Phantom One: Mark Twain the Optimist?

The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.

In the piece in question, the writer attributed this quote to Mark Twain, but, as an editor with a long background in literary study and some expertise in Twain, the quote just didn’t feel right to me. For one thing, it’s way too optimistic to jibe with Twain’s typically cynical stance toward human nature. So I took the usual first step and Googled the quote to see if I could get a sense of where and when Twain might have uttered or written that sentence. What appeared in my Google search was a very long list of entries, mostly from popular “quotations about everything” sorts of websites, all attributing the quote to Twain. The problem was that not a single one of those hits–not one— mentioned an actual source. By “actual source” here, I mean a concrete reference to a published work of Twain’s in which that sentence can be found, or a speech of his where it was recorded.

While the vast majority of attributions were to Twain, my Google search also revealed a number of other attributions, mentioning a host of other names, most of which I hadn’t heard of.

A search of a digital archive of Twain’s works revealed nothing.

Finally, doing a little more digging, I came to one of the better online resources for all things Twain, the Center for Mark Twain Studies (hosted by experts at Elmira College in New York), and found a fascinating article on this very quote. The writers of that article confirm that this quotation is one of the “most viral” quotes misattributed to Twain they’d ever researched, and they list some of the major sources that helped make the Twain attribution popular, including the epigraph to the 2014 Denzel Washington thriller The Equalizer. The article also mentions a dozen other popular “life coach” authors to whom the quote has been attributed, but locates the “explosion” of the quote’s frequent repetition to a popular 2011 Tweet by comedian Steve Harvey. The article also mentions another useful source for attributing dodgy quotations like this, Garson O’Toole’s Quote Investigator, which finds a likely original source for the quotation in a sermon published in 1973.

The most likely story is that a relatively little-known pastor penned a similar phrase for a 1970 sermon, which was eventually published in 1973. Various other sources must have picked up on the quote and repeated it, and then Harvey’s 2011 Tweet really got the quote circulating on social media, where it was picked up by many more authors and “influencers.” Along the way, someone attached the quote to Twain, and the attribution simply stuck because the attribution to Twain makes the whole quote sound, at least initially, more authoritative.

Phantom Quote Two: Wisdom of the Ages, from A Cartoon Character

A second quote in the same manuscript was similarly problematic. This time, the quote read “Yesterday is history, tomorrow is a mystery, today is a gift, that’s why it’s called the present.” The writer attributed this to Family Circle cartoonist Bill Keane. As with any quotation, I wanted to verify and document this, so, once again, I started with the old “Hail Mary” Google search to see what would arise. Again, the attributions were wide and variable, and included Keane, often referenced Eleanor Roosevelt, and even–by far the most popular attribution–the character of “Master Oogway” from the animated movie Kung Fu Panda.

Once again, it was Quote Investigator to the rescue. It found that “The earliest strong match located by QI appeared in a speech delivered at a graduation ceremony in June 1993 at Rutgers Preparatory School in New Jersey. The speaker was a member of the Board of Trustees, but he credited an unnamed journalist.”

The article was tentative about even that attribution.

Here again, we have what’s probably a popular aphorism of dubious or unknown provenance, and one that likely gets attached variably to whatever well-known figures make it seem more authoritative in any given moment.

Phantom Quote Three: Moses Said What, Now?

This one’s a little trickier. In this case, the writer quoted what they referred to as a “psalm,” which read, “One can chase a thousand, and two and ten can put ten thousand to flight.” The writer explained this to mean “you can do great things on your own.”

Now, this one set off alarm bells for me right away, partially since I was a very well-churched kid, so this “pinged” right away as a Biblical quotation, albeit not one I could immediately place. My first stop in this case wasn’t a broad Google search, then, but a search on the well-known Bible Gateway website, which allows users to search a collection of just about every major English translation of the Bible. That search directed me to Deuteronomy 32:20, which reads (in the NRSV translation):

How could one have routed a thousand

and two put a myriad to flight,

unless their Rock had sold them,

the Lord had given them up?

So, sourcing for the quote wasn’t a problem–its provenance was clear. But looking at the full passage in situ revealed it to be what I sometimes call a “Princess Bride quote,” that is, one where “I do not think it means what you think it means.”

Notice, first, that the writer had somehow gotten hold of an adulterated, incomplete version of the quote: “One can chase a thousand, and two and ten can put ten thousand to flight.” Despite a number of searches using various strategies, I could not find a single English translation that phrases the passage in exactly that way. Again, this is not a criticism of the writer: it’s surprisingly easy for these kinds of issues to slip into works-in-progress. One can misremember a phrase, jot down a quote incorrectly in one’s notes, or even unconsciously reword a quote in one’s passion to emphasize a particular idea. And, precisely because writers are passionate about their ideas, it can be legitimately hard for a writer to spot this kind of problem in their own work. That doesn’t mean the writer is a poor writer. It only means that the writer, like any other, needs an editor!

The problem with this particular misquote comes when one looks at the entire passage from which the quote is derived. In the context of the story being told in this part of Deuteronomy, the quote is from a poem “recited” by Moses to his followers near the end of his life. He’s feeling that his end is near, and worries that his people will stop following his lead (and, worse, stop following God) once he’s not around anymore. So he “preaches” to them in the form of a poem in which he imagines God, at some projected future time when Moses’ people have been unfaithful, speaking to them about the consequences of their unfaithfulness. One of the consequences Moses imagines is that God would allow a rival people-group to conquer them by routing them in battle–and, of course, if God decided to support the other guys, he could arrange things so that only one or two enemies (with God’s help) could rout the entire Israelite army all by themselves. So the meaning of the passage in question is basically “How could one or even two of those pipsqueak rivals have routed thousands of you (Israelites) in combat unless God had purposefully abandoned you?”

So the idea, here, is that Moses’ people could never take care of themselves without God’s help. Notice that this is the exact opposite of the writer’s interpretation (“you can do anything”).

The potential consequence of such a misquote is that the Bible is a pretty well-known text, so many savvy readers may realize that the quote is misused and misinterpreted, undermining their sense of the writer’s credibility.

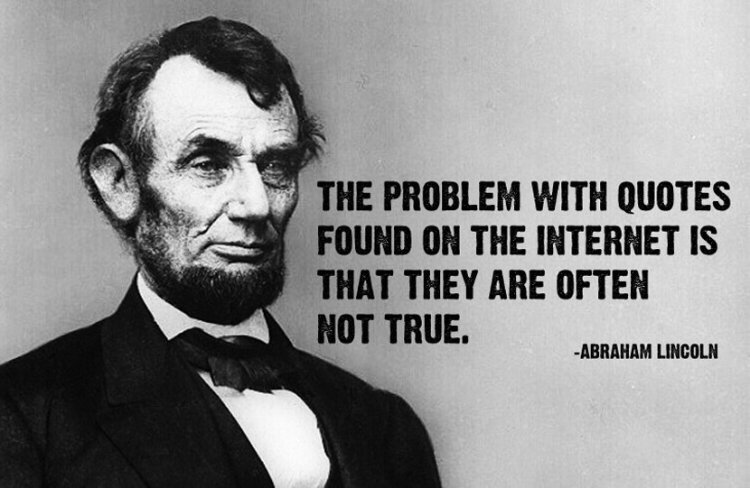

One immediate takeaway from all three of these examples, especially for beginning/inexperienced writers, is that doing broad, topical searches on Google to “find quotations” can be a dangerous practice. Such searches draw most of their results from popular websites that merely collect quotations circulating on the internet, and while they’ll usually attribute the quote to a person, they never do the homework necessary to provide the original sources of the quotations they list. Such quotes are often misquoted, very often misattributed, and, of course, are always presented in isolation with no context, which can easily lead to embarrassing misinterpretations. As I’ll explain in more detail in future posts, it’s usually much better not to search for quotations online at all, but rather to quote from what you know: from your own knowledge, reading, and research. That’s the best way to guarantee that your quotes will truly enhance what you’re saying and avoid potential damage to your readers’ sense of your credibility.

More broadly, all three of these quotes–and many, many more like them–led me to the thought that I’d love to be able to refer beginning writers (and maybe some experienced ones) to a resource that covers the basics of quoting well: When to quote, when not to, how to quote responsibly, how and where to source your quotes, how to attribute them properly, etc. My next several posts will be such a resource.

So, if you’re a new-to-intermediate writer, what else would you like to know about quoting well? If you’re a fellow editor, what kinds of dodgy or interestingly misused or misattributed quotes have you come across in your editing adventures? I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

2 thoughts on “Unmasking Phantom Quotes: A Guide for Writers and Editors”