[Note: Having spent the last number of posts concentrating on the tools and hardware we use for writing, I decided to switch gears for a while and talk a bit about matters of reading for a few posts.]

I’ve always thought that, as an editor, one of the most important things I can bring to the table is my long experience as a scholar of literature. After all, anyone can memorize a style manual or a set of grammatical rules. It’s something else to know not just what works in English, but why it works, based on extensive experience of the whole historical tradition of writing in English, from its roots in Old English to the present. What we write in English isn’t just about a set of rules, but about that long tradition, and the many cultures, events, and movements that have imbued English with its expressiveness and dynamism.

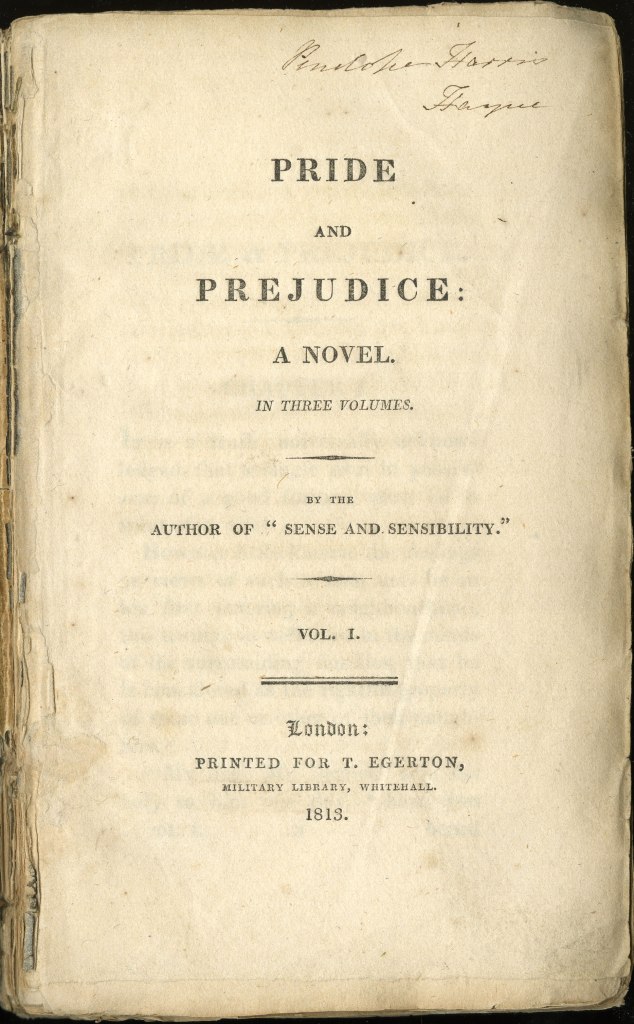

As a teacher of literature, too, I’ve encountered a lot of questions about the value of engaging with that tradition. Why deal with all that “old stuff?” What’s the use of bothering with Beowulf, or Chaucer, or Shakespeare, or Jane Austen, or any of those crusty “classics” we’re told, for some reason, we’re supposed to read? I’ve also encountered a lot of what one might call “literary abuse,” where someone had a terrible experience with a “classic” work because it had been used on them like a blunt instrument. Where some sadistic teacher, somewhere down the line, had decided that Dickens, for some reason, was just good for you, in the way that, I dunno, bran or castor oil are good for you, and, dammit, you’d better choke them down no matter how bad they taste.

But, you know, it’s odd. Of all the works one might call “classic literary novels,” I’m not sure I’ve ever really come across one I’d classify as “tedious.” There are some that I have felt as tedious at one time (I remember feeling that way the first time I read Wuthering Heights), but I can’t think of a single instance where that didn’t turn out to be about me rather than the novel: often I just wasn’t ready for it, and the sense of tediousness came from my own lack of understanding or maturity. When I encountered those novels later, they spoke to me like crazy. As a really stark example, I remember trying to read Moby Dick in junior high, and just being bored and bewildered (what’s all this crap about whale trivia?). But in college, I read it in a class where I was guided by a wonderful professor who helped me understand what was really going on, and that time it was everything but tedious. I was also mature enough to understand more sophisticated humor, and was astonished to realize that the book that I’d found tedious was, as a college junior, making me laugh out loud all the time!

These days, the only books I find tedious are the ones that really don’t have anything to say: formulaic romances, tired “sexy” books (Fifty Shades of Gray was the yawner of the century as far as I’m concerned—about as sexy as dry-humping a cardboard box), emo teen fiction (I tried to read the first Twilight novel and was asleep by the second chapter), and stuff with clear sectarian agendas (John Eldredge’s Wild at Heart just made me groan about four times per page).

I’d say there are a couple of keys to reading “classic” novels. One is that, especially for stuff written before the second half of the 20th century, it’s important to realize that they were written for people who tended to have more leisure time, and for whom books were a more expensive investment. A beach-read thriller that you can blast through in three hours would have made a 19th-century reader feel robbed. They’re meant to be taken slowly. So when you read them, it’s important to just kind of relax into them, read as long as feels good. Put the book down when you find yourself tiring of it. It doesn’t matter if it takes you six months or a year to get through it. Just roll with the book’s own pace and don’t try to speed it up and make it something it’s not.

Also, it’s perfectly fine if you’re reading a novel and just finding it frustrating, to put it down. There’s no reason to force anything. Sometimes it’s just not your time to encounter that novel yet, and that’s okay. But I’d encourage you not to dismiss a novel just because of that experience. Hang on to it. Wait until the impulse to try it comes back around (which it probably will). Sometimes a novel that has nothing for you at 25 can speak to you like crazy at 40. Don’t assume it’s a terrible novel just because your first encounter isn’t what you hoped. Just stick it back on the shelf. One day you’ll come back around to it and it might be incredibly meaningful. If you never get back around to it, that’s okay too. No one’s obligated to love a novel just because it gets labeled a “classic.” Just donate it to your local public library, and maybe it’ll speak to someone else.

Just don’t stop reading.